We are daughters, sisters, wives, mothers, nieces and aunts to someone, and as such are mentioned in the genealogical records, but it seems that history has to a large extent been able to

do without the functions of women that go beyond those determined by biology. Having become aware of such an underrepresentation of women in history books, two young female historians - Irene Franken

and Edith Kiesewalter – founded the ‘Cologne History Association for Women’ in 1986, in order to scrutinize historical documents, note and files in the archives of town halls and museums, and dig up

and bring to light a few more talents displayed by women in the past and present.

They have been quite successful. A decision taken by the town council was reversed as a consequence of the ardent and eloquent pleading by these lady historians, whose group has meanwhile grown to

the imposing size of fifty members, and has built up a high reputation for themselves.

It had been decided that Cologne’s city hall tower is to be decorated with 124 statues of historical figures who have been of relevance to the town. Only five of these statues were to represent

female historical figures. The well-founded research work undertaken by our historians has convinced the council that altogether 18 ladies are now worthy of giving company to the 106 male historical

figures!

Three roads have been renamed on account of the group’s initiative. One is called the ‘Irmgard Keun Straße’, after a successful female writer who lived in Cologne. The second is called the

‘Seidemacherinnengäßchen’, named after a powerful women’s guild for spinning silk, which had established itself in Cologne in the Middle Ages. The third road, called ‘Katharina Henoth Straße’,

reminds us of a brave and talented woman who took up the business of Postmaster General after the death of her father and who was too efficient and competent not to arouse envy among her rivals. She

was denounced as a ‘witch’ and burned in 1627. It is presumed that the rival family clan Coesfeld was behind the denounciation.

But a precise proof has never been found, and the spirit of the day was such that only with the help of the devil could a woman become so powerful and capable. Prejudice and superstition

prevailed in those dark ages, where the forces of nature were overwhelming and could not be understood. Katharina Henoth’s courage in the face of so much ignorance and evil-mindedness will now be

honoured. Her statue will be placed on the city hall tower.

Perhaps the ‘Cologne history association for women’ has also inspired the artist

Ms. Langenbach to create a fountain portraying women of various historical periods in Cologne. Beginning with the woman of the Ubier, a Germanic tribe that had originally settled on the right-hand

banks of the river Rhine, before the Romans came. Next to her stands the woman of Cologne, the newly established city ‘Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensis’ during the Roman period (around 50 A.D.). So

it continues through the ages to the present day, showing the influence exercised by many powers, such as the Franks – another Germanic tribe with many settlements on the continent – the Dutch, the

Italians and the Prussians. Situated in one of the most expensive residential districts of Cologne, this colourful fountain shows that Cologne has absorbed many cultures and nationalities, and the

forceful posture and appearance of the portrayed personalities suggest that women have had more than just a supporting role in shaping our history.

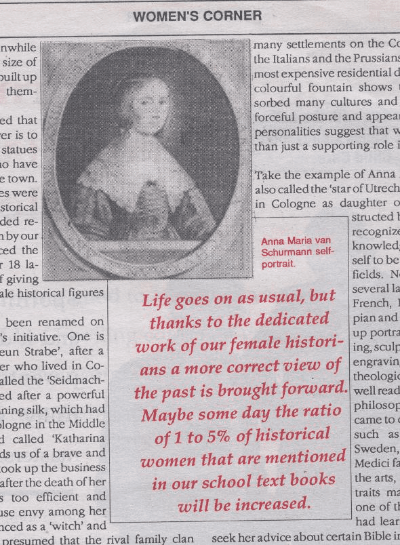

Take the example of Anna Maria van Schurmann, also called the ‘star of Utrecht’. She was born in 1607 in Cologne as daughter of a Dutch family. Instructed by her father, who had recognized her great

thirst for knowledge, she revealed herself to be quite a genius in many fields. Not only did she learn several languages, such as Latin, French, Hebraic, Syrian, Ethiopian and others,…she also took

up portrait painting, wood carving, sculpturing and copper plate engraving. In philosophical and theological affairs she was so well read, that the famous French philosopher, René Descartes, came to

consult her. Royal guests such as Queen Christine of Sweden, or the famous Italian Medici family, a great sponsor of the arts, came to have their portraits made, or to converse in one of the many

languages she had learnt. Protestants came to seek her advice about certain Bible interpretations, since she was able to refer to the original text. She was able to fight her way into the university

of Utrecht in Holland, something very unique for a woman in those days. The ‘star of Utrecht’ was made. At the age of 35 she was first mentioned in an encyclopedia. Anna Maria van Schurmann was the

idol of women, she was their shining example.

But she had benefited from the protection of her family. And could it be that her success is also due to the fact that her father had fostered her rather worldly talents, and had in fact

asked her to promise him never to get married? She willingly fulfilled his wish, and lived to a high old age.

In her own birth town, however, she was forgotten for many centuries, until our group of lady historians brought her life’s work back to memory. Her sculpture is soon to adorn Cologne’s town

hall.

Life goes on as usual, but thanks to the dedicated work of our female historians a more correct view of the past is brought forward. Maybe some day the ratio of 1 to 5 % of historical women that are

mentioned in our school text books will be increased. History is a very interesting subject, but her story is not bad either!

SPECIAL FEATURES

FAMILY MATTERS NO LONGER MATTER MOST IN EUROPE

GLOBE magazine, Pakistan, September 2000

“Children sweeten labours, but they make misfortunes more bitter”

Francis Bacon, English Renaissance author (1561-1626)

By Cornelia Renee Schwaller

“Children are the wealth of a society” it used to be said. It seems that these days in Europe the wealth is with a different group of society - the ‘silver’ generation, the ones with naturally grey

or white hair. This is the group of people that sometimes hit the front page of German national newspapers with words such as: ‘Germany soon to have the second-oldest population world-wide.’ The

recently published leader was based on the prognosis which says that in 30 years’ time Germany will have 34.4% of its population aged above 60. Italy will by then even have 37.7% of its population in

this age group. In some European countries, every second person is older than 40. By comparison, every second person in some developing countries in the world is below the age of 15.

What’s happening to the ‘old continent’ Europe? It seems to be doing justice literally to this term. The 375 million inhabitants of the 15-member states that belong to the European Union are ‘growing

old together’. The average age of the inhabitants of Europe is at present 39 and rising by two years every decade.

This is higher than that of any other region in the world. In the 1990s, fertility levels were around two thirds of replacement level or even lower. Yet possible extinction is still centuries away.

Assuming the unrealistic and absolutely hypothetical forecast that the fertility and mortality rates remain constant in Europe and that there is no increase due to migration, the computers project

that there will be just some 50,000 Europeans around in the year 3000!

Countries in Eastern and South Eastern Europe are experiencing a similar decline in fertility rates. By itself, Western Europe’s total fertility rate for 1998 was 1.6 children per woman. together

with countries of Eastern Europe, including the Commonwealth of Independent States, the total fertility rate for 1998 is brought down to 1.5 children per woman. The political and economic

difficulties which the East European countries have had to encounter after the fall of the Berlin Wall and the opening of the former iron curtain that divided Europe, have left their mark. The number

of births registered in 1998 for Bulgaria and Bosnia-Herzegovina, for instance, has decreased to 1.1 per woman.

Western Europe in the seventies saw the introduction of the ‘anti-baby pill’. technically, this made contraception reliable for the first time. Soon there was a noticeable decline in the number of

births. But what are the reasons behind such an altered trend in people’s behaviour?

Have Europeans lost their stamina and drive? Is the famous individualism of Europeans, not unknown in the past for their spirit of adventure and discovery, turning into pure egoism and

self-indulgence? Does materialism gain the upper hand on people? Is it the knowledge that a life-time’s work will anyway secure an old-age pension even without having children? A very illusory piece

of information as is now known. The stiff competition through the effects of globalisation and the subsequent flexibility which is demanded on European’s labour markets must also be leaving their

marks on the family planning of couples. These are all just some of the factors behind Europe’s demographic trend.

Alternately, could it be that Europeans are simply looking ahead into the future and being sensible about their personal family planning? News of the escalating run on ever-diminishing resources

world-wide is possibly having an effect. So is the expansion of the computer-aided industries that make so much of the work formerly performed by humans simply unnecessary.

It has often been suggested that people would rather invest in pleasures for themselves than in children. They would rather buy another car than have another child, rather watch TV than change

nappies. The extra leisure time couples have today is not being spent with children. Having children is defined as work. Yet these services carried out at home are not only unpaid, their social

recognition is considerably lower than for those activities and services carried out in the public and private sectors.

Whether childbearing, and especially child-rearing, will become favoured leisure-time activities of women and men will depend on the trade-offs between fun and burden. Unless the burden of having

children is diminished or the rewards of having children are enhanced, the balance for childbearing will continue to be negative.

Of course, the way men and women plan their private lives should really be up to them. Yet officials, sociologists and politicians need to look ahead and be aware of demography when planning new laws

to ensure that society is not upset by too great imbalances.

The European Observatory on Family Matters has issued a publication behalf of the European Commission as part of the series ‘Employment and Social Affairs’. Although the Commission has no direct

competence in the area of family policy, it has increasingly turned its attention to examining and understanding the social and economic implications of new trends in society on families. Within the

framework of its policy on equal opportunities for women and men, in particular, the Commission has undertaken several initiatives aimed at reconciling work and family life. The study compiles

country reports and new scientific insights, and comes to a number of conclusions:

The developments since the Second World War do not help to anticipate future demographic trends. During the so-called ‘baby-boom’ of the early 1960s, most West European countries had fertility rates

of above 2.5 children per woman. This was followed by a rapid fertility decline in the 1970s, bringing the West European average down to about the present rate of 1.6 children per woman.

According to 1998 statistics, the lowest fertility rates in Western Europe are in the South European countries: Spain, (1.16 children per woman), Italy (1.2), Greece (1.3). Portugal is at level with

Germany with 1.35 children per woman. Ireland and France have the highest fertility rates. Ireland enjoys Europe’s highest economic growth rate of 5.75%, permitting a more active family policy. Its

scheme to pay families with three or more children might be considered pro-natalist, whereas in fact this measure was introduced to support poorer families with more children. National identity, too,

might play a large role here in influencing the wish to have children. Fears related to the ethnic composition of the population, in-group-out-group feelings can be powerful emotional forces. In the

case of Ireland, there is a clear rivalry between two population groups — the Catholics and the Protestants — that may attempt to outnumber each other.

Similar phenomena may be found in Israel between the Jewish and the Arab population groups and before 1991 in the Baltic States between the Baltic population and the Russians. However, there are also

strong counter-examples such as French-speaking Canadians, non-Hispanic Californians, or Germans living in cities with many Turks. Here ethnic-linguistic rivalry is carried out by means other than

what can be called ‘reproductive behaviour’.

Within the EU, France currently is second only to Ireland in high birth rates. France’s pro-birth family policy is a century old, and it has had a clear pro-birth intention with its child support

schemes. And yet the rate of divorce has quadrupled since 1965 (from 10 to 40 per cent in 1997). Yet the French are about to rediscover the benefits of family life. It has been frequently said: “The

best way to sell a vacuum-cleaner in France today is to show a man vacuuming his home.”

Greece is the EU Member State with the most pronounced concern about low fertility. The apprehension about low and further-decreasing fertility seems to go across the entire political spectrum. This

may be also connected with rapid population growth in neighbouring countries. Greek family policies now focus on the promotion of larger families. Child allowances have been raised by considerable

amounts.

In a European comparison in the 1990s, Sweden was the country with the largest decline in fertility. With some 2.14 children born per woman in 1990, the rate dropped by around 30% to 1.54 children

per woman in 1998. This decline coincided with a measure taken by the Swedish government to reduce the national budget deficit, resulting in considerable cuts in local budgets, which again decreased

the purchasing power of families. A sharp decline in birth rates due to a budgetary policy was also noted in Austria. An allowance of 1,090 Euro per child was dropped as of January 1997: 10 months

later, the monthly birth rates dropped by 10% and have remained at that lower level ever since.

One recent trend that has often been singled out as a dominating feature of societal change is women’s increasing independence. Over recent decades, female participation in the work-life has steadily

increased in virtually all industrialised countries. According to a recent opinion survey, 75% of all Europeans believe that women should contribute to the family income. In Germany, around 60% of

the total workforce are women. The increase has been strongest in Scandinavia, where workforce participation is almost universal among adult women below age 50. Economic independence of women also

tends to result in a postponement of marriage, which typically is associated with lower fertility.

Yet one must be cautious in relating the two factors. It may also be that the lower number of desired children motivates women not to stay at home, or there may be a driving force behind both trends.

The latter possibility is supported by evidence from several countries experiencing improvements in fertility rates despite very high and still increasing female labour-force participation.

Sociologists have found out that women and men are increasingly reluctant to make decisions that have long-term consequences and clearly limit their future freedom of choice. Marital stability has

declined in all industrialised countries. Women are no longer economically forced to stay in an unsatisfactory union if they earn an independent income. Whatever the social and psychological reasons

may be, the chances of a young couple staying together for 20 years — the minimum time required to raise a child — are slimmer than they were in the past. Responsible prospective parents may decide

not to have children if they are not absolutely sure about the stability of their partnership, as increasing evidence from empirical studies shows that the separation of parents actually does more

harm to children than had been assumed in the past.

After the Second World War, the so-called German ‘economic miracle’ provided the financial background for the development of social security systems - and in particular of old-age pensions. Prior to

this war, having children was traditionally seen as a vital investment in one’s own future. Increasingly, children have lost their paramount function for income maintenance in old age. This has

created the illusion of secure and foreseeable pension entitlements accruing after decades of life at work and payments towards the state and company pension schemes. Moreover, public pension schemes

favour people without children, rather than those men and women who care predominantly about their offspring.

A shrinking workforce will, however, have to pay an increasing part of their salary for a growing army of grey heads. There is currently a heated debate in Germany about the generation contract and

the more equal burden-sharing of securing income for the elderly. From a child-centred perspective, the generation contract has to be extended and revised. The government has seen the need to

subsidise the additional private pension savings that the younger generation will need to set aside in order for themselves to have a secure income in old age. A committee has also been set up to

examine to possibility of introducing a law on immigration.

A different kind of approach towards the family has been practised with considerable success in the Netherlands. A great part of the employment sector is based on part-time work. Just five per cent

of all women with children work at a full-time job. Only 29% of the Dutch believe that women should contribute to the family income — quite unlike other West Europeans. It is their opinion that a

single breadwinner’s salary is enough to provide for the partner and two children. Most women stop working altogether or reduce their working hours when they have their first child. The government

has many cabinet members who are models of pro-family orientation. One minister is well known for taking his children to school in the morning and insisting on sharing his dinner with them.

In the former Socialist countries, fertility rates could be influenced more directly. For instance, the 1976 pro-birth measures taken in the German Democratic Republic - East Germany. They are

estimated to have increased the number of births by 20 per cent. This was partly due to the fact that there had been a shortage of housing. Getting married and having children was the only way for

young men and women to get their own flat. These are not exactly measures that can be introduced in democratic, pluralistic countries.

Will there be a trend reversal in Europe one day? Or is the European example one that will be followed by other countries in the world soon? A lower reproduction rate can also kindle positive

associations. Many more square kilometres for people to live in. Plenty of houses and flats. Fewer traffic jams, less polluted air and purer water. If on the other hand the present trend continues,

the number of human beings walking on this earth might double from the present six billion to an estimated 12 billion human beings in 50 years. What kind of a national and international organisation

will it need to guarantee them enough space, to distribute water, food and shelter to all of these? Is there time to act before reality takes decisions out of the planners’ hands? In Europe and

elsewhere.